Hammer & Hope is The New Magazine Focused on Race and Class

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death in May 2020, there was lots of talk in the mainstream media about the possibility of police and prison abolition, with publications such as the New York Times and The Atlantic joining the conversation. Since then, while organizers across the country have continued to fight toward this goal, debate and talk about abolition in the media has certainly died down. Hammer & Hope, a new publication founded by Jen Parker and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, recently arrived to directly confront these issues.

Launched in February of 2023, Hammer & Hope is a magazine of Black politics and culture that borrows its name from scholar and historian Robin D. G. Kelley’s 1990 book, Hammer and Hoe, which follows Black Communists in Alabama during the Great Depression. In their welcome letter, the two cofounders outline their vision and name the communities and thinkers who inspired it, from the Black Panthers to renowned author Toni Morrison, who once famously said that “if there’s a book that you really want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

Parker, a former editor at the New York Times who edited notable progressive editorials such as Mariame Kaba’s call for police abolition and Caroline Randall Williams’s essay on Confederate monuments, and Taylor, an author, professor at Northwestern, and contributing writer at the New Yorker, connected in 2020 when Parker edited Taylor’s writing for the Times. The two had several conversations about the gaping holes in coverage of race and class in mainstream media. In 2021, they began to write out their vision and mission statement for the publication that eventually became Hammer & Hope.

Parker told Teen Vogue that, while she sees publications like the socialist feminist magazine Lux as a sister publication to Hammer & Hope, she thinks Hammer & Hope is contributing something particular to journalism. “I think our focus on race and class differentiates us from our peers,” she said. “From our perspective, there’s really no meaningful coverage of Black life, or of working-class and poor life in mainstream media. So, when mass protests occur like they did in 2020, there may be a flurry of articles, but no systemic effort to understand the root of what drove people to the streets, or how this moment fits into a larger historical context. Hammer & Hope wants to get to the roots of the crises that plague us, so we can better understand our world.”

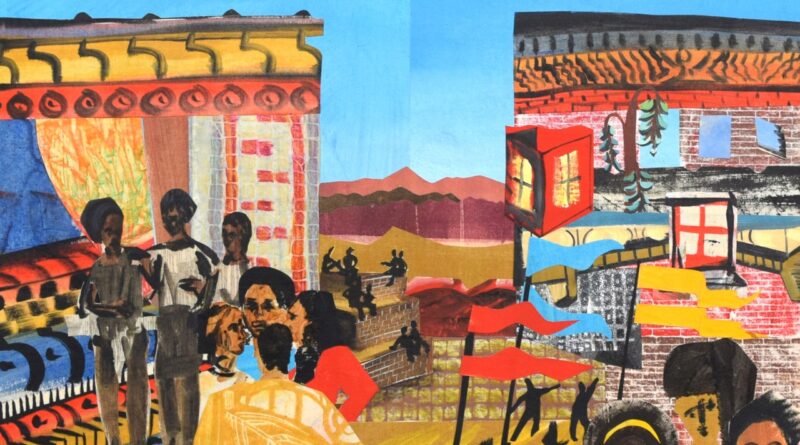

Hammer and Hope’s first issue covers a range of topics, including a denouncement of urban renewal policies in St. Louis, an explainer on the importance of freeing former Black Panthers from prison, and a long-form essay on the importance of the work of multidisciplinary artist Faith Ringgold. Some of the magazine’s contributors, such as Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and Derecka Purnell, are established writers and academics; others are activists and organizers to whom Hammer & Hope has given a new platform. Parker and Taylor agreed on the importance of giving organizers a platform at the magazine and, when deciding what pieces to include in the first issue, Parker noted that it was “less about the writers and more about the pieces.” She continued: “It’s important for us to publish organizers talking about their own organizing and sharing tactics. For example, a lot has been written about the Kansas City Tenants. But now you get to read 5,000 words of the organizing story from their own perspective, and other tenant unions can learn from it.”